In recent years, the uncontrolled spread of the Cochineal, Dactylopius coccus (Cochinilla del Carmin) has led to the near disappearance of the prickly pear (higo chumbo) in Spain. So lets explore our lost heritage: cochineal and the endangered prickly pear in Spain

Historical Significance

The introduced prickly pear (Opuntia maxima), originating from Central America, has played a vital role for centuries. It served various purposes, including being a source of food (prickly pears, higo chumbos), livestock feed, agricultural support, slope stabilization, and hedges.

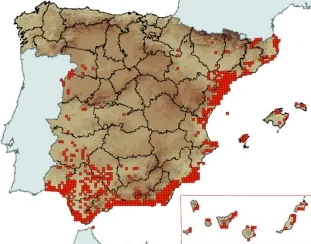

Cultural Impact and distribution in Spain

Historically, it has been a lifeline in arid regions of the southern and southeastern Iberian Peninsula, alleviating hunger. In the Canary Islands, it is cultivated for cochineal extraction, holding a designated origin certificate since 2016. Cochineal dye, a natural colorant (E-120) with carminic acid as its main component, finds applications in the food industry, cosmetics, pharmacy, and more. The color varies based on its interaction with acids, bases, or the formation of aluminum salts (carmine).

Historical Roots

Cochineal farming traces back to pre-Columbian times in Mexico, later exported to the Canary Islands and other compatible climates. Its economic importance was substantial, replacing or complementing other dyes in the market post the discovery of America.

Rise of Cochineal as a Plague

In Spain, however, cochineal has evolved into a plague. The aggressive strain, considered a wild species within the same genus, has strayed from the carefully selected strain used for centuries in dye production. It is suspected to have escaped its intended use as a biological control measure, leading to considerable controversy. Since 2009, the prickly pear has been on Spain’s official list of invasive species.

Controversy and Perspectives

While some see this infestation as a natural remedy to eradicate invasive exotic cactus species (similar to the situation with the agave weevil), others, myself included, argue that prickly pears have been an integral part of our landscape for centuries. We believe that, at the very least, the specific species (Opuntia maxima) and its variations can be preserved in locations where they have traditionally thrived and been cultivated.

Spider habitat

the Tent-Web Spider – Cyrtophora citricola – Araña orbitela de las chumberas

In Spain it was once very common to see their webs in prickly pears (Opuntia), where they often grouped together, ranging from a few individuals to colonial webs of several meters in length with many hundreds of spiders. The Spanish common name for this spider even uses the prickly pear, Chumbera!

However, in recent years and with the uncontrolled spread of the Cochineal – Dactylopius coccus – Cochinilla del Carmin the prickly pear habitat for this spider has all but been lost across the Iberian Peninsular. Read more about this lovely spider here: https://wildsideholidays.co.uk/tent-web-spider-cyrthophora-citricola-arana-orbitela-de-las-chumberas/

Cochineal and the Prickly Pear in Spain: Frequently Asked Questions

The prickly pear is disappearing in Spain largely because of the uncontrolled spread of cochineal (Dactylopius coccus). This insect feeds on the cactus sap and, in its aggressive form, causes plants to collapse within months. Since around 2009, the damage has accelerated, especially in southern Spain. Although cochineal was once economically valuable, this wild strain has tipped the balance, leaving landscapes bare where dense hedges once stood.

Cochineal is a scale insect historically farmed to produce carmine dye, known as E-120. It arrived from the Americas centuries ago and was carefully managed, particularly in the Canary Islands. However, a more aggressive strain appears to have escaped control. As a result, cochineal shifted from prized resource to invasive pest, devastating prickly pear populations instead of supporting traditional dye production.

Not originally. Although prickly pear (Opuntia maxima) was introduced from Central America, it became deeply woven into rural life. For generations, it provided food, livestock fodder, boundary hedges, and erosion control. Only in recent years was it officially classed as invasive. This classification remains controversial, especially in areas where the cactus has shaped local culture and survival for centuries.

Cochineal dye was once among the world’s most valuable natural colourants. Derived from dried insects, it produces deep reds used in textiles, cosmetics, and later food and medicine. After the discovery of the Americas, it transformed European markets. In the Canary Islands, cochineal farming even earned protected designation status in 2016. Ironically, the same insect now threatens the very plant that sustained this trade.

The decline of prickly pear has quietly disrupted local ecosystems. A striking example is the tent-web spider (Cyrtophora citricola), once common in chumberas. These spiders built large communal webs among the cactus pads. With the cactus gone, their habitat has largely vanished across the Iberian Peninsula. Fewer webs now dot the countryside, a small but telling sign of wider ecological loss.

Preservation is possible, but it requires nuance. Some experts argue cochineal acts as natural control against invasive cacti. Others believe traditional varieties like Opuntia maxima deserve protection where they have long coexisted with people and wildlife. Targeted conservation, careful monitoring, and local cultivation may allow prickly pears to survive without repeating past mistakes. The full debate is far from settled.

I’ve been living in this lovely area of Western Andalucia for the last 20 years or so and dedicate most of my time to the running of English language tourist information websites for the towns of Cádiz, Ronda, Grazalema, the famous or infamous Caminito del Rey, and also Wildside Holidays, which promotes sustainable and eco-friendly businesses running wildlife and walking holidays in Spain. My articles contain affiliate links that will help you reserve a hotel, bus, train or activity in the area. You don’t pay more, but by using them you do support this website. Thankyou!

I think the article could be clearer if you explained that Dactylopius coccus* is an insect.

Fun fact, the dwarf kermes oak (Quercus coccifera*) known locally as ‘coscoja,’ is the habitat of the kermes insect, another natural source of crimson dye ( from Arabic- qirmiz, qirmizī).

*Coccum/ κόκκος ‘berry.’

Cordially,

Thats interesting Arthur!

Hi Clive, thanks for this article. I am starting a project about the global history of the prickly pear. Would you be open to sharing some of the references you used to write this article? Many thanks!

I live and work a small farm in western Andalusia. For us the prickly pear cactus is the bane of our lives, the problem being that, where it grows on a slope, it eventually falls over and regrows where it lands thus spreading itself rapidly and requiring us to clear it from around olive trees. The clearing of it is an extremely unpleasant job due to its prickles and becomes a constant battle. True – it forms an effective fence and firebreak, but don’t let it grow on a slope.

Thank you for covering the topic. I miss the green cacti in the andalucian landscape. Seeing the black carcasses that remained from them in 2016 was heartbreaking.

You are welcome Jan! I miss the street sellers in Ronda with their ready peeled and ready to eat higo chumbos!